This article is more than one year old. Older articles may contain outdated content. Check that the information in the page has not become incorrect since its publication.

Dubbo Go Review and Outlook

Dubbo is a high-performance RPC framework open-sourced by Alibaba in 2011, which has significant influence in the Java ecosystem. On May 21, 2019, Dubbo graduated from the Apache Software Foundation and became an Apache Top-Level Project. Currently, the graduated Dubbo project’s ecosystem has officially announced the introduction of the Go language, releasing the Dubbogo project. This article is a complete review and genuine outlook of the Dubbogo project, collaboratively completed by Yu Yu from Ant Financial and Fang Yincheng from the Ctrip R&D Department.

1 Dubbogo Overall Framework

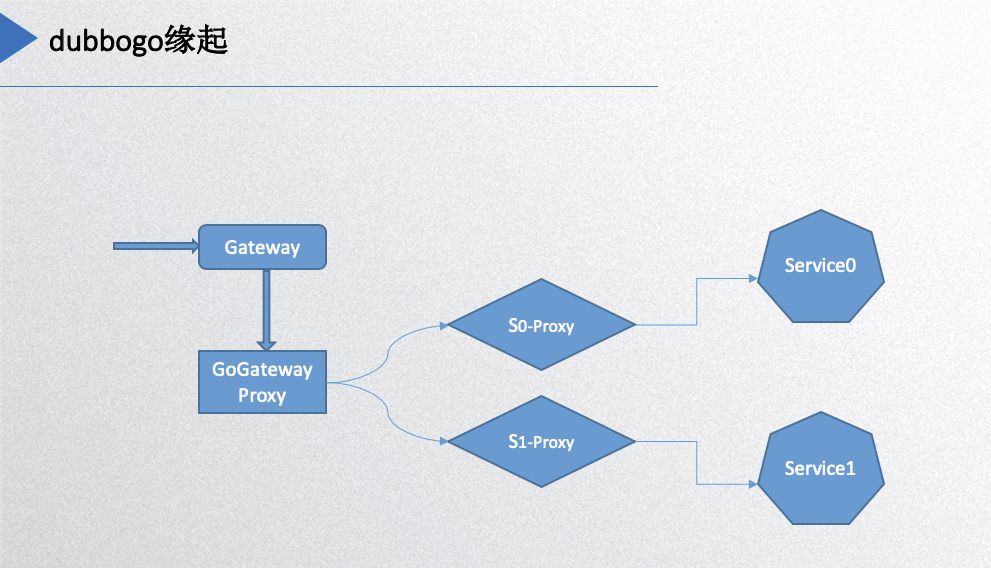

Let’s start with the origin of Dubbogo, illustrated in the following diagram:

On the far right, service0 and service1 are Dubbo’s servers, while the gateway on the left is where HTTP requests enter. They must be converted to the Dubbo protocol before reaching the backend services, so a proxy layer is added for this function. Essentially, each service needs a proxy for converting protocols and requests, leading to the requirement of the Dubbogo project. The initial implementation was aimed at achieving intercommunication with the Java version of Dubbo.

Dubbogo Goals

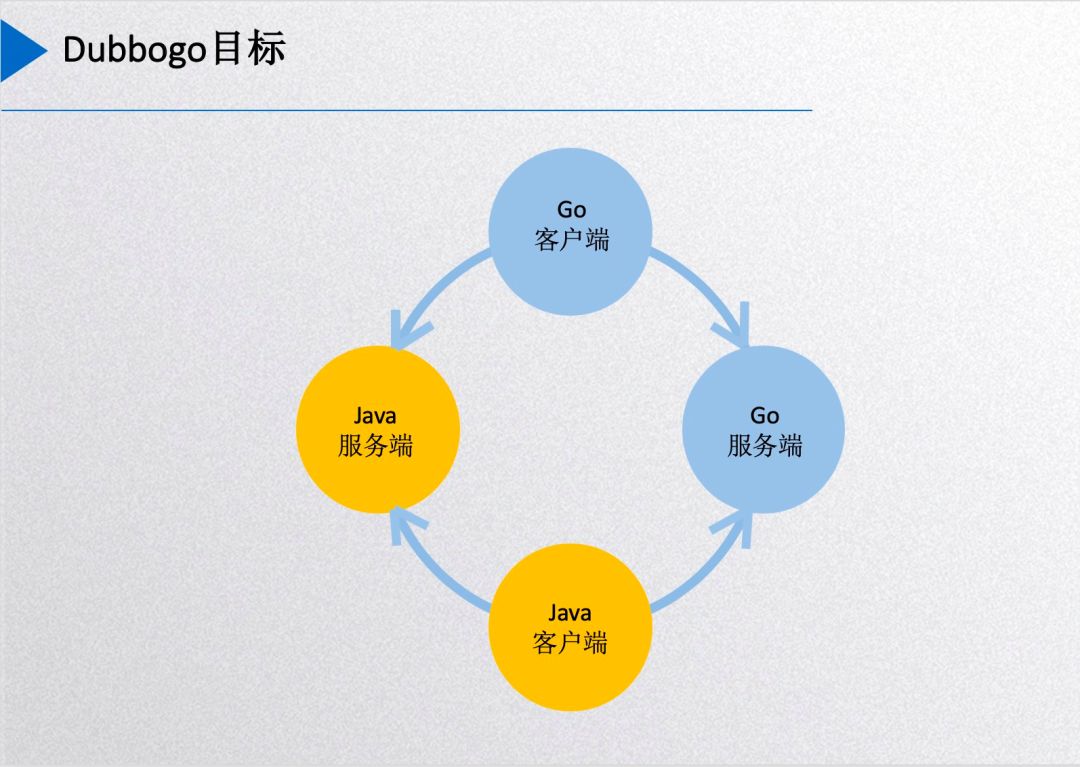

The diagram above illustrates Dubbogo’s current goals: using a single Go client codebase to directly call endpoints in other languages, primarily Java server services and Go server services. Furthermore, when Go acts as a server, Java clients can also directly call Go server services.

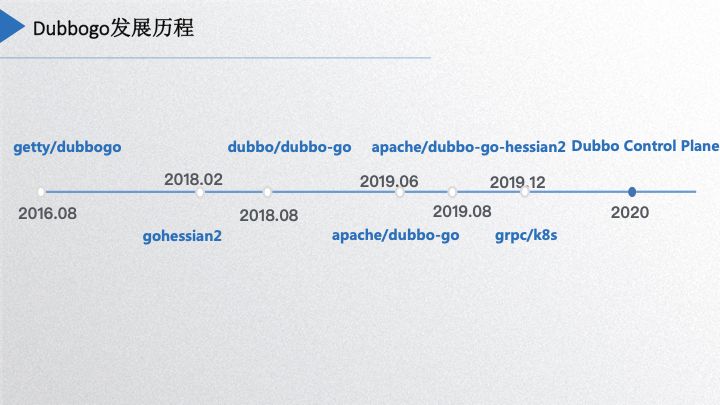

Dubbogo Development History

Next, let’s introduce the entire development history of Dubbogo. In August 2016, Yu Yu initiated the Dubbogo project, which at that time only supported HTTP communication via the JSON-RPC 2.0 protocol. By February 2018, it supported TCP communication through the Hessian2 protocol. After being officially recognized by Dubbo in May 2018, a complete reconstruction began from scratch. In August 2018, Yu Yu completed the preliminary refactoring, yielding version 0.1. Due to some demands from Ctrip, my colleague He Xinming and I began participating in the Dubbogo project’s restructuring. In June 2019, Dubbogo 1.0 was launched, which incorporated the primary features designed according to Dubbo’s overall architecture. During the same period, the project entered the Apache organization. In August of this year, the Dubbo-go-hessian2 project, led by community member Wang Ge, also entered the Apache organization. By now, our community has been aligning its work with Dubbo in various aspects, such as supporting gRPC and Kubernetes, with related code currently under review. The v1.3 version, slated for release by the end of the year, will include gRPC support. By 2020, our goal is to enter the cloud-native era with a renewed approach.

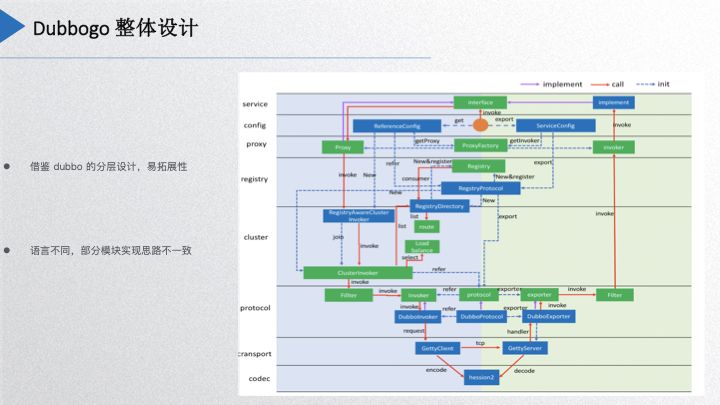

Dubbogo Overall Design

This diagram may look familiar; it is Dubbo’s layered architectural design. However, it lacks many components found in Dubbo. We borrowed Dubbo’s layered design and extensibility concept, but the inherent differences between Go and Java necessarily led to some simplifications in our project design, particularly at the protocol layer. For instance, the SPI extension in Dubbo has been adapted using Go’s non-intrusive interface approach. Additionally, due to Go’s prohibition of circular package references, Dubbogo enforces strict structure in code packaging and layering, aligning with its extensibility attributes.

For the proxy part, since Java has dynamic proxy capabilities, Go’s reflection capabilities are not as robust, thus leading to a different implementation of the proxy here.

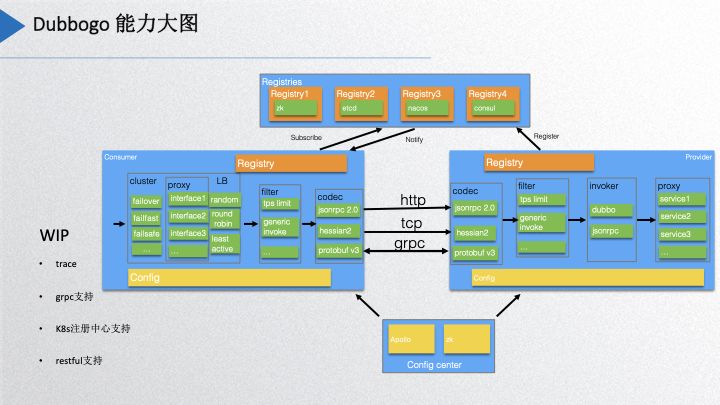

Dubbogo Capability Overview

The above image displays the current capabilities of our Dubbogo project. At the highest level, we have supported several registration centers, including Zookeeper, etcd, Nacos, and Consul. We are currently developing features associated with Kubernetes. The configuration center now supports Apollo and Zookeeper. On the consumer side, it has implemented cluster features and strategies that cover nearly all strategies supported by Dubbo. Additionally, load balancing strategies and filters mainly include TPS throttling and generalized calls, which will be discussed later. The coding layer currently includes JSON-RPC 2.0 and Hessian2, while Protobuf v3 is under active review. The community is currently developing support for features including tracing, gRPC, Kubernetes registration center, and RESTful support.

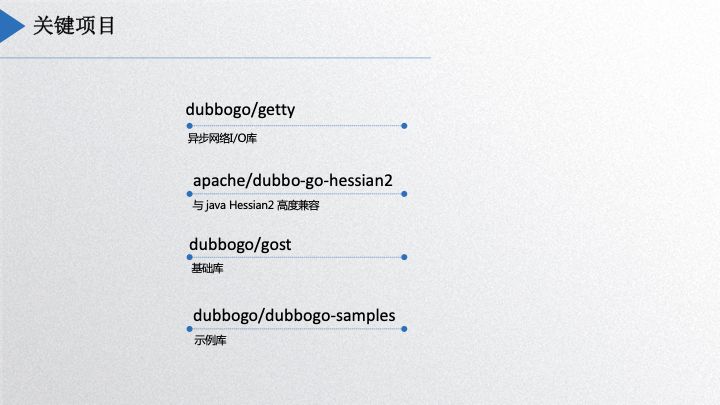

Key Projects

The Dubbogo project currently consists of four main components: the first is Getty, an asynchronous network IO library, which serves as a solid foundation for implementing TCP communication protocols; the second is dubbo-go-hessian2, which is highly compatible with the current Java Hessian2; the third is GOST, which is the base library for Dubbogo; and finally, the Dubbogo examples library, which has recently migrated to https://github.com/apache/dubbo-samples, merging with Java examples. These constitute the main components of Dubbogo.

2 Protocol Implementation

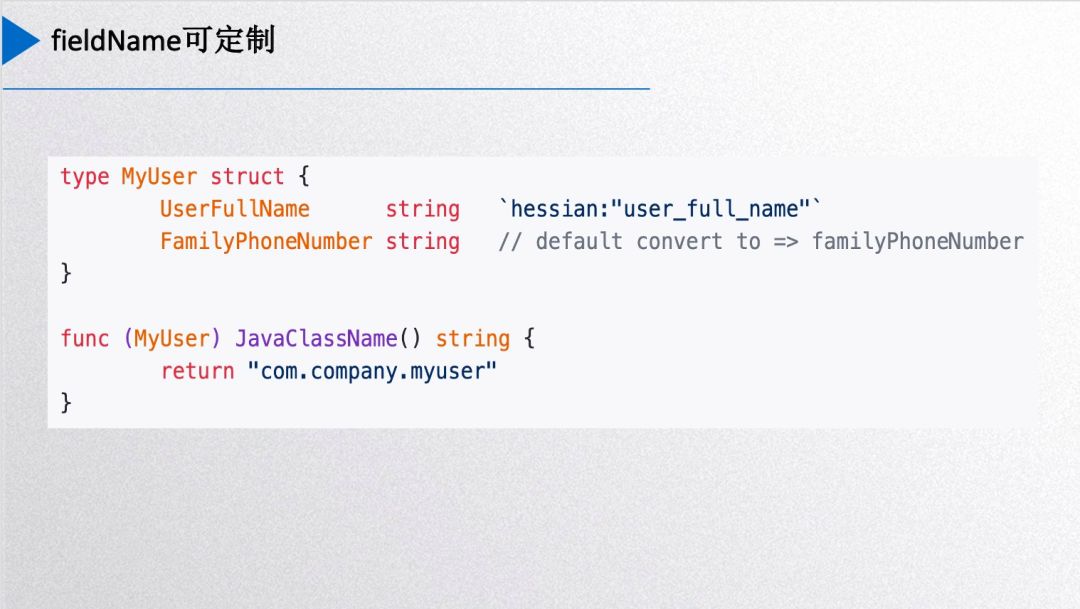

Next, let’s discuss some specific implementations and functionalities. The above image illustrates Dubbogo-hessian2’s implementations, highlighting some of its key features. The first is the implementation of Java’s JDK exceptions, supporting over 40 types of Java’s primary exceptions, enabling mutual decoding and encoding support with Java’s Hessian2 version and allowing for automatic extension of user-defined exceptions or less common exceptions. The second is the support for field name aliases; Go’s serializable fields start with capital letters, while Java defaults to lowercase, which raises issues of inconsistent encoded field names; hence, there’s alias recognition that allows for custom naming.

Go-hessian2 also supports Java’s BigDecimal, Date, Time, basic type wrappers, Generic Invocation, and Dubbo Attachments, and even emoji support.

For user-defined types in go-hessian2, users must register them, provided that these comply with Go-hessian2’s POJO interface for proper encoding and decoding with corresponding Java classes.

The above shows the type correspondence table of go-hessian2. It’s worth emphasizing that the int type in Go differs in size depending on the architecture—32-bit or 64-bit—while Java’s int is fixed at 32-bit. Hence, we map Go’s int32 to Java’s int.

As previously mentioned, there’s correspondence between Java’s Class and Go’s struct. The above diagram outlines the POJO interface definition in go-hessian2, demonstrating that each Java class corresponds to a Go struct, requiring the struct to specify the Java class name.

You can also add Hessian tags. During parsing, this field name will be used as an alias, enabling custom field naming. By default, go-hessian2 automatically converts the first letter of struct fields to lowercase as their field names.

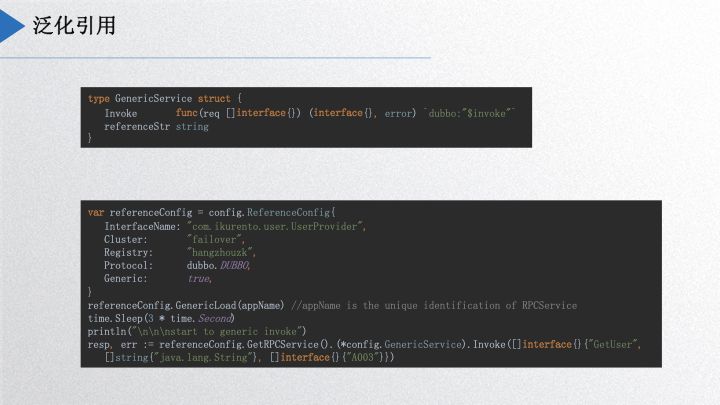

The generalized reference is an important feature in Dubbogo. A community member needed to implement a gateway based on Dubbogo to collect external requests and then call other Dubbo services using the generic reference approach. Upon implementation, it first involves embedding a GenericService service within the project, calling Load, and then proceeding with a standard service invocation, similar to Java. Go clients can effectively invoke Java services without knowing the Java interface and class definitions, simply passing method names, parameter types, and a parameter array in map format to the Java server, which will process the request and convert it into a POJO class.

Above are some details concerning go-hessian2. The previously mentioned generic reference turns the gateway into a public consumer for all internal Dubbo services, requiring only knowledge of the method name and parameter types to call Dubbo services. Moving forward, the main focus will be on three areas: first, the network engine and underlying network library; second, service governance, which includes a preliminary solution for using Kubernetes as a registration center; and third, interoperability, particularly with gRPC. Lastly, we will provide an outlook, outlining the community’s tasks for the upcoming year.

3 Network Engine

Dubbogo’s network engine consists of three layers, depicted in the diagram below:

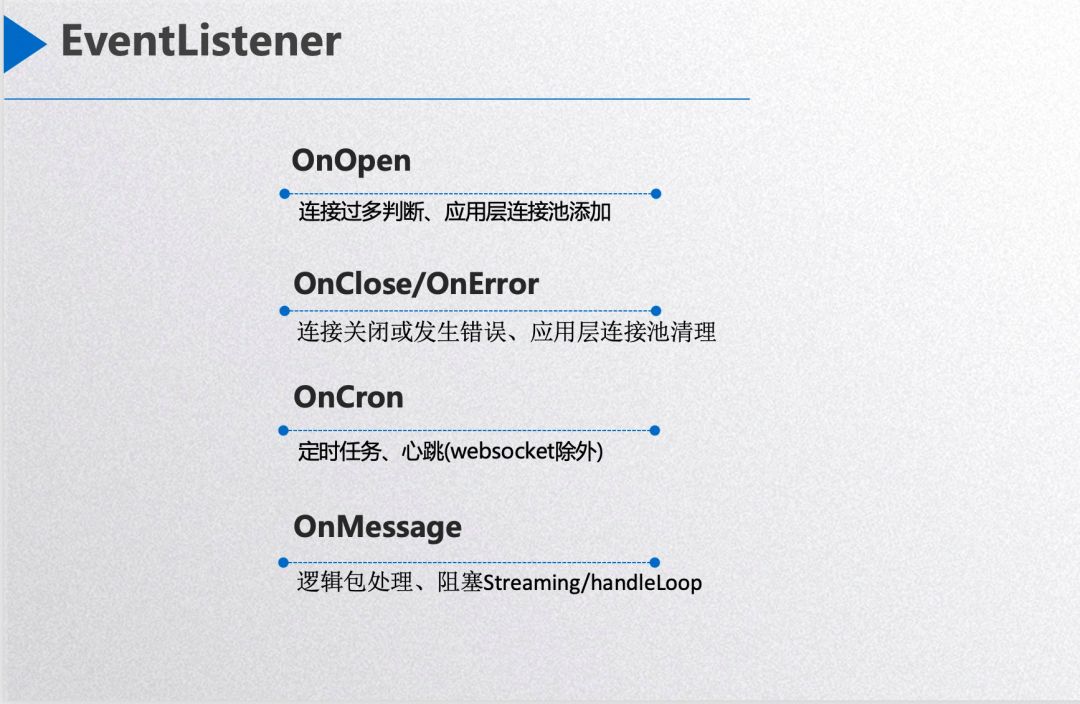

The bottom layer handles streaming of binary data, the second layer is the codec layer, responsible for protocol serialization and deserialization, and the third layer is the Event Listener, which provides interfaces for application use. The streaming layer supports WebSocket, TCP, and UDP communication protocols and offers considerable flexibility. Earlier this year, a community member in Shanghai added KCP; he stated the intent to open source it, and I’m looking forward to that. The codec layer can accommodate different protocols as users define.

EventListener exposes four callback interfaces to the upper layer. The first is OnOpen, which is triggered when the network connection is successfully established. The application layer can store the connection session if determined to be valid; otherwise, a non-empty error response will cause Dubbogo to close that connection. Next is the OnError event, which calls this interface when a network connection error occurs, allowing users a chance to handle it before Dubbogo closes the connection, such as deleting the network connection session from the application’s session pool. The third is OnCron, handling scheduled tasks like heartbeats. Dubbogo automatically manages heartbeats at the lower layer for the WebSocket protocol while requiring users to implement this themselves in the callback function for TCP and UDP protocols. The fourth interface is OnMessage, which processes an entire network packet. The overall callback interface style closely resembles that of WebSocket interfaces.

Goroutine Pool

Dubbogo’s goroutine pool comprises worker channels (quantity: M) and logic processing goroutines (quantity: N) along with network tasks (network packets). After unpacking the network data, packets are placed into a worker pool according to certain rules, and logic processing goroutines read from the channel and execute logic processing which separates network I/O from logic processing. Depending on the design, N may vary, which can be categorized into scalable and non-scalable goroutine pools; Dubbogo employs a non-scalable pool to limit maximum usage of network resources.

Additionally, Dubbogo’s goroutine pool does not consider the order of packet processing. For instance, upon receiving packets A and B, Dubbogo may process packet B before packet A. This is acceptable if requests are independent and not sequential. If order matters, A and B can be merged or the goroutine pool’s features can be disabled.

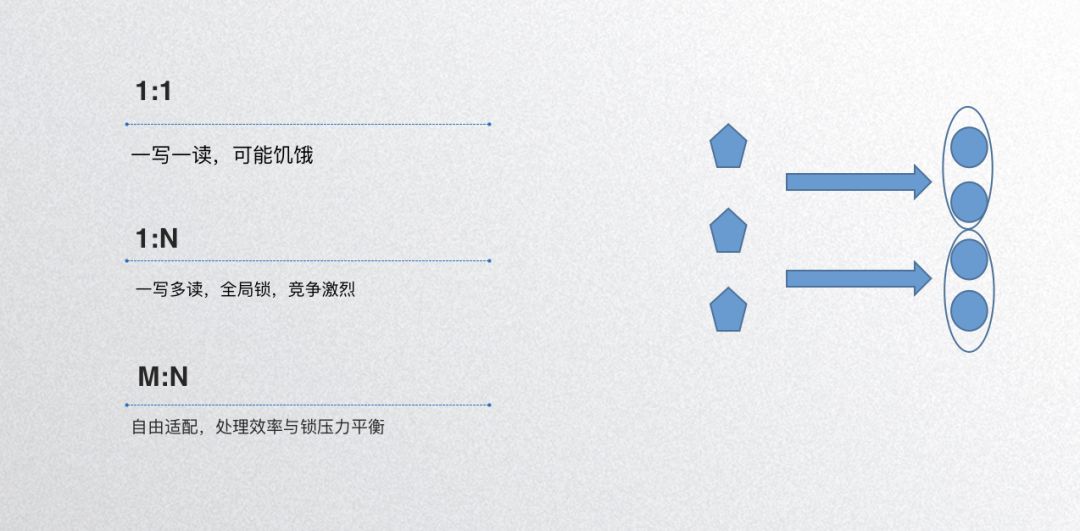

Generally, it is not advisable to implement your own goroutine pool as Go has advanced resource management for goroutines; released goroutines are not immediately destroyed but can be quickly reused, minimizing cost. A reasonable case for using a goroutine pool may include scenarios where similar tasks are executed repetitively, but careful consideration of the M to N ratio is crucial.

Assuming certain network tasks take different durations to complete—some finished in 1 second, some in 10 milliseconds—setting an M to N ratio of 1:1 could lead to starvation, causing some queues to process too quickly while others lag, resulting in an overall unbalanced load.

Another ratio model is 1: N, which involves one producer and multiple consumers. As you have only one queue with one producer and multiple consumers, it could cause inefficiencies due to Go channels’ lower efficiency from mutex locks, leading to consumer goroutines hanging due to lock contention, thus impeding packet order guarantees.

An ideal model is when both M and N exceed 1. In Dubbogo’s goroutine pool model, M and N are configurable and each channel can be consumed by N/M goroutines, akin to Kafka’s consumer group. This balances processing efficiency and lock pressure, leading to overall task processing equilibrium.

Optimization Improvements

Optimization and improvement are approached from three aspects:

- Memory Pool: The goroutine pool manages CPU resource allocation while the memory pool manages memory resource allocation. I personally oppose creating a memory pool purely for show; Go’s memory management is already well-optimized. The initial versions of Go used Google’s tcmalloc, which cached freed memory before releasing it, leading to high memory costs. If a sidecar program has resource limitations, potential memory use is problematic. The latest Go memory manager is entirely reconstructed and effectively manages memory without uncontrolled inflation issues. However, if certain objects in your business are reused frequently, consider employing memory pools. Most memory pool technologies rely on sync.Pool and implementing one isn’t overly complex. After Go 1.13, sync.Pool seamlessly manages cached objects across GC spans.

- Timer: Early Go timers were inefficient due to a global lock. The latest timers improve this by assigning a timer for each CPU core, distributing contention pressure. However, there can still be contention issues; if time precision isn’t critical, a simple timer implementation in your application is recommended to relieve CPU pressure.

- Merging Network Write Buffers: Buffer merging typically utilizes writev; however, Go’s writev has memory leak issues identified by a colleague developing MOSN. He submitted a PR to the Go team and then removed writev from MOSN, replacing it with a simple buffer merging mechanism that reads packets from the send channel in a for loop, merging and sending them. If there are insufficient packets in the send channel during the loop, it exits through the

select-defaultbranch.

Channel Usage

Go is suited for handling IO-intensive tasks but is less effective for CPU-intensive tasks. Its core memory communication method is through channels. A channel’s memory structure is essentially a ring buffer array and a lock, in addition to various read and write notification queues. However, due to the use of a single lock, improperly using buffer channels can yield inefficiencies, such as overly large memory usage per channel element. Channels also have a closed field to indicate if writing has been closed; erroneous usage can lead to 100% CPU cycling in for-select loops.

4 Service Governance

Now, let’s discuss service governance, where service discovery and registration are paramount, logically similar to Dubbo, which I won’t elaborate on. This section mainly covers two topics: rate limiting algorithms and graceful exits.

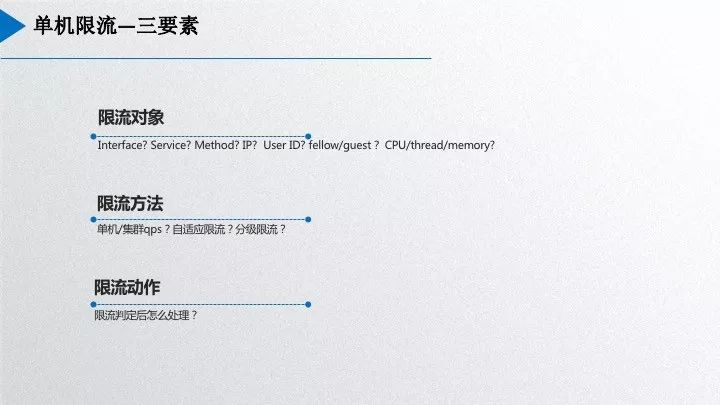

Rate Limiting Algorithms

Rate limiting first necessitates consideration of its targets, focusing on interface and method in Dubbogo. Next is the rate-limiting approach; one must determine if it’s for single-node or cluster encapsulation, with single-node limiting algorithms varying greatly, including common fixed and sliding window algorithms, as well as adaptive rate limiting. A significant challenge in rate limiting is parameter setting, including determining reasonable machine resource use for online services and acceptable duration for limiting time windows; QPS values must also be configured reasonably. Dubbogo aims to address these challenges. Advanced algorithms like Google’s BBR help proactively adjust parameters before network conditions worsen. Various business forms may also require tailored rate limiting, differentiating between member and non-member workflows.

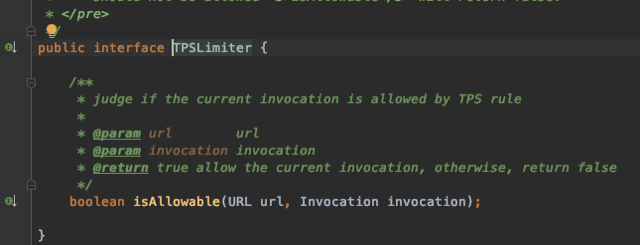

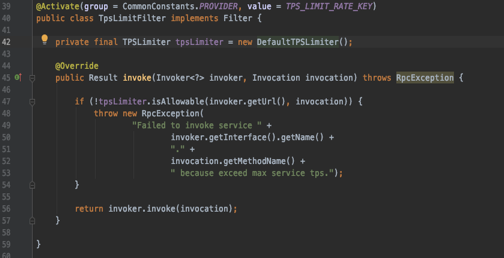

The source code for Dubbo’s rate limiting interface is as follows:

This interface abstraction is elegantly structured; it defines the limiting URL and service call. Below is the source code for Dubbo’s fixed window limiting:

Clearly, “private final” restricts Dubbo users to the predetermined fixed window limiting algorithm, preventing extensions.

Here’s Dubbogo’s rate limiting interface:

TpsLimiter defines the limiting object, TpsLimitStrategy specifies the limiting algorithm, and RejectedExecutionHandle defines actions taken during limiting.

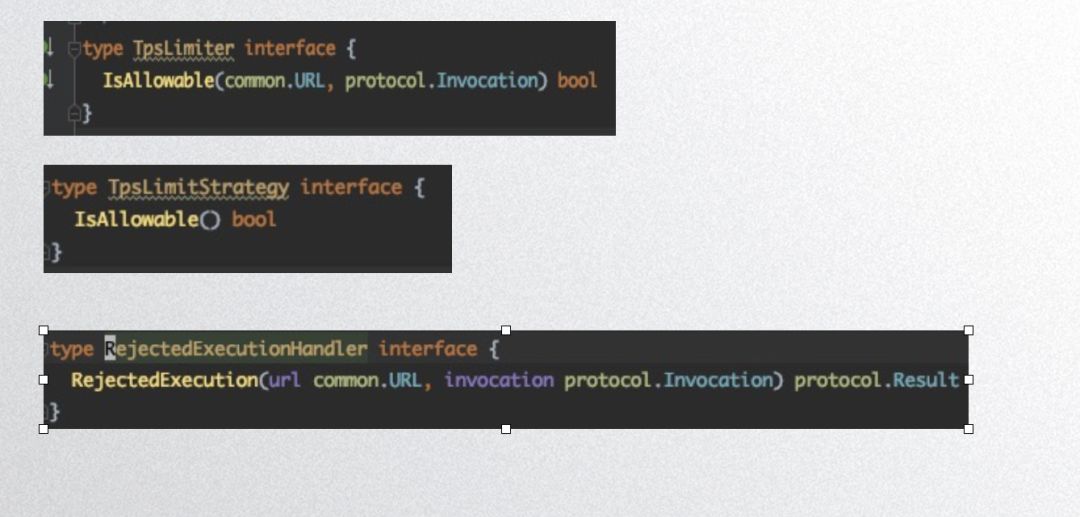

Next is a fixed window algorithm implementation:

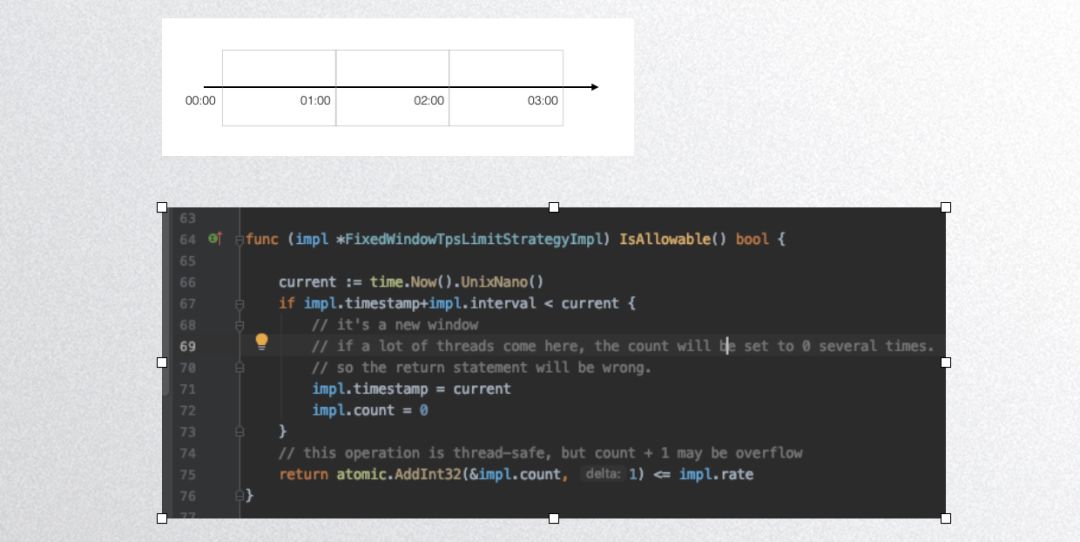

The above code displays Dubbogo’s fixed window algorithm implementation, which is not thread-safe; this implementation is not recommended for public use. Below is Dubbogo’s sliding window algorithm implementation:

Its core principle is to use a queue to store requests within a specific timeframe, allowing determination based on queue length.

Regardless of the fixed or sliding window, the determination algorithms are straightforward, with complexity often lying in parameter settings:

Precision control for fixed window length is challenging. For instance, if QPS is 1000 within a second and the first 100 milliseconds receive 1000 requests but are rejected into subsequent non-processing, the effective solution is to refine time granularity. Dubbogo’s time window’s minimum unit is one millisecond, thus allowing a time window of 100 milliseconds for comparatively smoother request processing.

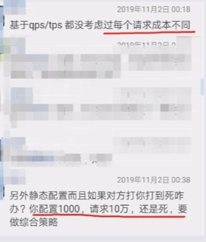

In the image below, our community committer Deng Ming published a blog which received comments from industry experts via WeChat:

The first question highlighted questions QPS and TPS due to varying costs per request. A potential solution is implementing tiered rate limiting, applying different handling across various requests under a single service. The second question raised “configured QPS of 1000, yet 100,000 incoming requests create failure.” In this case, higher level operational capabilities are necessary—blocking potential malicious traffic at the gateway or expanding server capabilities if performance is insufficient.

For tiered rate limiting, Dubbogo currently cannot be executed within the same process. It necessitates refinement within the Dubbogo configuration center. Users could establish multiple service pathways for varied client memberships; for instance, distinct pathways for member/non-member services could evaluate if a userID is a member at the gateway.

Dubbogo’s single-node circuit breaker is implemented based on hystrix-go, with parameters including maximum concurrent requests, timeout, error rate; along with a protection window defining how long to circuit-break. The third aspect involves protective actions for executing during the protection window, allowing user customization.

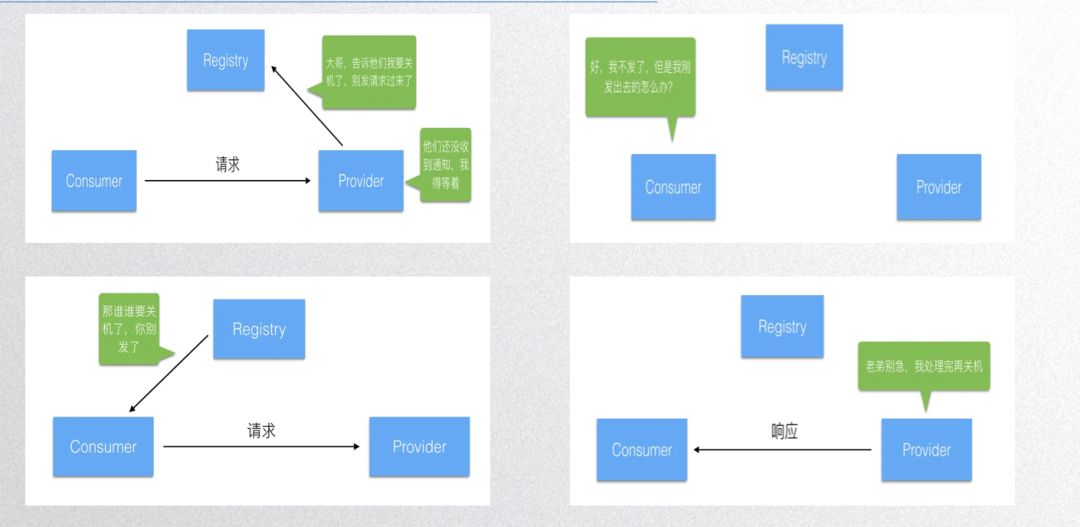

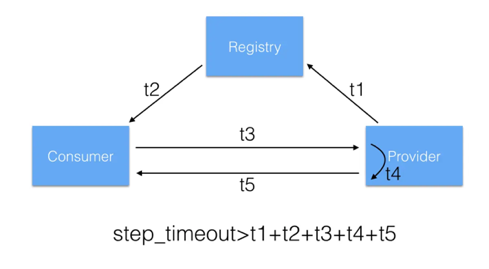

Graceful Exit

Deng Ming’s thoughtful work also covers graceful exit, and related blogs can be found online. Steps for gracefully exiting are:

- Notify the registration center that the service will close, while waiting to process requests;

- The registration center notifies other clients to stop sending new requests while waiting for responses for previously sent requests;

- Once the node has processed and returned all received requests, it releases server-related components and resources;

- Finally, the node releases client components and resources.

Each step requires the program to allocate a certain amount of time; the default in Dubbogo is approximately two seconds per step, totaling a ten-second window.

Such handling is relatively rare in other RPC frameworks.

5 Dubbogo in the Cloud

Dubbogo enters the cloud as a microservice framework that requires adaptation to Kubernetes and deployment strategy. While Dubbogo functions as an RPC framework, it also encompasses service governance capabilities that overlap with some Kubernetes capabilities—complete abandonment of which isn’t feasible. As there is no strong solution from the Dubbo team, we present a basic practical approach below.

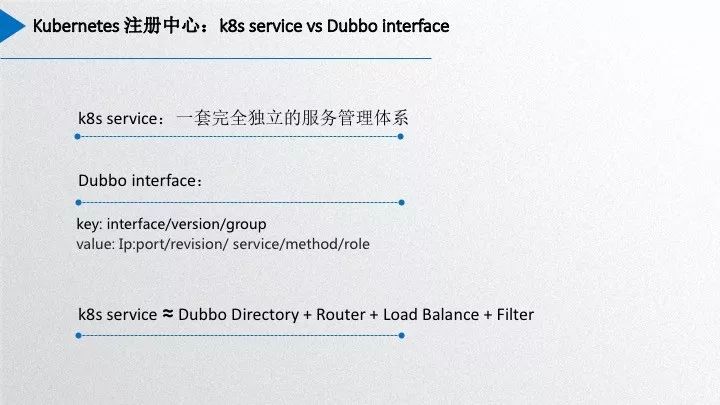

First, let’s analyze the distinctions between Dubbogo’s interface/service and Kubernetes service.

Kubernetes service aggregates pods with similar capabilities, having its load balancing algorithms and health checks. Meanwhile, Dubbo’s interface/service merely associates with service provider collections, relying on additional governance modules like directory, router, and load balancers. Furthermore, Dubbo distinguishes between group/versioning, as well as provider and consumer roles. Due to these significant differences, direct alignment between Dubbo interface/service and Kubernetes service isn’t achievable.

Kubernetes provides resources at three levels: pod/endpoint/service. A simple approach could involve listening to events within pod/endpoint/service tiers to apply reasonable handling for governance purposes. Currently, community member Wang Xiang has submitted a PR to implement governance by listening to pod events, which requires no additional components by leveraging the most granular resources. By interfacing with Kubernetes API server to acquire pod lists while utilizing etcd for registration and notifications, continuity in Dubbo’s governance persists. This method is straightforward and requires minimal changes to Dubbo. However, it lacks the ability to utilize Kubernetes health check capabilities; detailed pod events must be monitored for service health assessments and status changes. Moreover, excess event listeners result in unnecessary network load on the API server.

As such, this may not be the optimal solution while slightly deviating from recommended operator methods. The community discussions are ongoing for refining new solutions, with a lean towards community-recommended operator schemes—but such implementations may rise maintenance costs. The two approaches will coexist, and decision-making will vary among users.

6 Interoperability

Regarding interoperability, Dubbo has three significant objectives for the coming year, one being connecting with the external microservices ecosystem, such as integration with gRPC. Currently, Dubbo’s gRPC solution is publicly available, and the development of Dubbogo’s connectivity with gRPC is nearly complete.

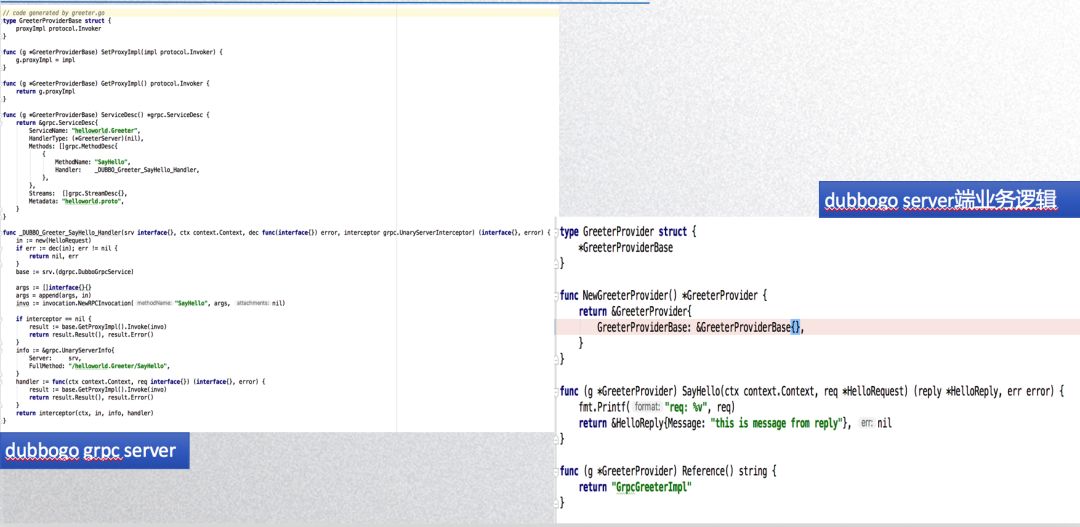

The image below shows a Dubbogo code generator tool that automatically creates Dubbogo-compatible code based on gRPC’s pb service definitions, alongside a corresponding usage example. Unlike the complexities of Kubernetes services, gRPC only encompasses RPC capabilities without governance features, meaning that raw gRPC can be effectively embedded within Dubbogo. The method handler from gRPC server becomes our Dubbogo invoker, directly integrating related gRPC interfaces.

7 Future Outlook

Finally, we look towards the future and outline plans for the upcoming year.

Next year, we aim to swiftly implement the Dubbo router. The community has already developed the foundational algorithm module for routing capabilities, but at that time, the configuration center lacked strong parameter transfer capabilities, leading to incompletion. Recently, governance configurations were enhanced to support Zookeeper and Apollo, suggesting that soon, router parameters may be delivered via configuration Centers. Furthermore, we will introduce a mainstream community tracing solution, using OpenTracing as a standard to integrate with the OpenTracing ecosystem. The third aspect pertains to Kubernetes operators, aiming for service invocation through operators to implement a new Kubernetes-centric registration center. Lastly, we aspire to assimilate into the cloud-native ecosystem, aligning with Istio for Dubbogo’s pivotal role within the service mesh environment.

Currently, Dubbogo is in a functioning state this year, but there remains substantial work to improve quality. Functionality will nearly meet Dubbo 2.7 compatibility by next year, with outputs proving sufficient for practical use across three representative companies: Ctrip and Tuya Smart, to name a few.

Dubbogo, as a Go language project, looks forward to insights and requirements from other Go communities for mutual growth.